By Kyra Gaunt

I am an ethnomusicologist by training but I also teach anthropology and black studies. Over the last six years, I have had an inconsistent curiosity about what I called the “unfinished migrations” of the relationships between African nationals in the U.S. and “African” domestic Americans living and making music in New York City. As an ethnographer who performs occasionally in this complex arena of diasporic identifications, it has taken a while for me to locate and describe the elusive connections on an intra-diasporic ethnography. Part of this work has been self-reflexive, examining how I myself travel between and am dislocated by my African friends and my African American cohorts.

My first experience performing “African” music was probably singing Kumbaya in my grandfather’s place of worship in the early 1970s, during the onset of the Vatican II folk masses. Or was it learning to perform Alunde Aluya, a cyclical oral song from noted choreographer, dancer, and anthropologist Pearl Primus (1919-1994), and her son, master drummer Onwin Babajide Primus Borde, as a doctoral student in classical voice, at the University of Michigan in the early 1990s? At the time it never occurred to me to ask what part of Africa the song was from.

Perhaps an arguably more bona fide experience occurred while learning to perform Agbekor, a dance-drum-and-song tradition of the Anlo-Ewe peoples of Ghana and Togo during my first year teaching at the University of Virginia. During the 1996-1997 academic year, I audited a white colleague’s African drum and dance ensemble that included both Ewe and forest people’s music from the Central African Republic. It was my first prolonged engagement with an African musical tradition. My colleague invited master drummers from Ghana in as visiting scholars. One was Fred Kwasi Dunyo and the other Dr. Alfred Ladzekpo, who had a Ph.D. from Columbia University. That year was my first experience interacting with contemporary African musicians. But you might think this is an exception, for most black music scholars, given the lack of publications discussing intra-diasporic connections between people not just sounds.

Back in 1993, when reading The Black Atlantic by Paul Gilroy for the first time, the absence of any discussion of African nationals, of actual people responding to or commenting from the side of the Atlantic gulf never even occurred as odd in a monograph centered on the African diaspora. I thought it was interesting how my grad school buddy from Physics, whose work lay outside cultural studies, was the first person to bring it to my attention.

Now fifteen years later, the inclusion of actual Africans in black musical discourse about “African Americans” is at best optional and at its worst obsolete—relegated to aural Kente cloth arranged in ringtones that sound African such as the majestic invention of the “Roots Mural Theme” (1976) by composer Quincy Jones. The sound samples enough of African and European idioms to connect the old and new across a gulf of time and place, conjoining what was lost with what could be found, without returning to an African coast or consulting an itinerant African artist.

What continues to displace our contact with actual Africans in black music studies as well as black popular television, movies, and theater is our discourse and fetish of Africanisms or cultural survivals—the remnants of what can be assembled as African are far more precious than interacting with living, contemporary people of recent African descent. That gulf, the displacement of language, dress, religion, and especially music, is too wide a chasm to cross.

In my opinion, Africanisms in music have been the defining trope used to re-member blacks to their African roots. Music has been the register renewing our membership into ethnic identities we longer know. I witness this displacement every time a hip-hop artist tries to legitimize the art of emceeing by closely aligning its contemporary practice with a mythologized interest in African griots. As my friend and colleague Joseph Schloss, author of Foundation: B-boys, B-Girls, and Hip-Hop Culture in New York, mentioned when we discussed the topic, trying to legitimize hip-hop “assumes that it isn’t already legitimate” on its own terms.

It seems like the only reason a majority of African American musical artists and scholars think of Africa at all is in claiming ancestry in an ethnocentric way. It reminds me of when I introduced my hip-hop students to the recording sampled by Bill Laswell on Herbie Hancock’s classic Headhunters album. When I tested them on the date of the recording, which was in the materials they received but never discussed, their aural imagination placed the singing in the 1500s, before the technology for recordings ever existed. In contrast, but bearing a similar mark, my anthropology students from over a half a dozen different countries, cannot accept that hunter-gatherers, who exemplify the earliest model of an organized human culture, still exist. Africans always seem intangible from the discourse we have set in motion since at least the colonial expositions of Ota Benga at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1914. But I digress.

African Americans seem to be blind to the recent descendent waves of African migration throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, who could also call themselves African American. How do we, and why do we, continue to exclude the more recent waves of immigration from our understanding of contemporary black music culture? Right here in New York City, one need not return to the slave or gold coast to experience diaspora as the outer boroughs of Harlem, Brooklyn, and the Bronx become increasingly populated by, for instance, Francophone Africans from Senegal, Mali, Cameroon, and Niger. In their work on the unfinished migrations of the diaspora, Tiffany Patterson and Robin D. G. Kelley leave us with a nagging question—”To what degree are New World black people ‘African’?” (2000).

In 2004, I went to Accra. It was my first time on the continent. Almost simultaneously, I began an informal study of the “unfinished migrations” within the African musical diaspora at an historic African American venue in Harlem, African Night at St. Nick’s Pub every Saturday. The Pub is located on what was once known as the “jazz corner” of West 149th Street at 773 St. Nicholas Avenue within the historic “Sugar Hill” settlement that defines the geography of the Harlem Renaissance. Before Harlem became “the black mecca” defined by its 1920s Renaissance of the arts, it was settled by Dutch, Irish and Jewish immigrants. Sugar Hill eventually became home to wealthy African Americans such as W.E.B. DuBois and Duke Ellington. Harlem was not only a “Negro” metropolis, it also featured new African, Haitian, and Cuban migration. (Johnson 1925 , 635).

My initial participant-observation over a nine month period from March to December of 2005 revealed what Ingrid Monson once referred to as the “imperfect attempts to cope with contradictions” within the African diaspora, as well as the “ongoing difficulty of improvising one’s way through a minefield of global forces” (Monson 2000, 17). Observing experiences at African Night at St. Nick’s interrupted presumptions I held about an inherent connection between Africans and African Americans. Connections were possible to a certain degree, yes. But solidarity during African Night seemed short-lived and polar, like the opposite ends of a magnet—connected yet constantly repelling the other end’s charge.

During my first visit or “return” to the continent, back in November 2004, I made the obligatory journey to Elmina Castle on the once famously named Gold Coast. I stood inside a dark cavern of the fort just two feet from the infamous “door of no return.” Standing there, I could hear the breaking waves of the Atlantic and glimpse its shore through the narrow passageway. I stood there facing a reality that I had only had the opportunity to imagine “Africa” and Africans though tales of the forced separation from drums, not land and resources. Makes me wonder sometimes if music has deflected us from the economic and political wealth left behind. In that moment, I was overcome by an inescapable sense of loss that was not what I expected. For the first time in my life, I was face-to-face with material evidence of becoming enslaved. That “door of no return” was the beginning of an end— the beginning of my ancestors becoming “Africans of the blood,” as Ali Mazrui put it, and the end to being an “African of the soil,” transplanting uprooted and rootless myths through stories, songs, and dance. What we’ve been left with, for lack of a better education, is a racial, biologically-determined connection divided by centuries of hypo-descent ideology, privileging whiteness over Africanness and it is this that drives my continued education and collaboration with African artists in Harlem.

Last year, I collaborated with Abdoulaye Alhassane Touré, the bandleader of African Night at St. Nick’s Pub. Touré is an extraordinary guitarist, a composer-arranger, and a multi-instrumentalist hailing from the Niger Delta basin from Gao, Mali to Niamey, Niger. I take two songs I had already written as R&B tunes and he and I re-arrange them for voice and electric guitar based on traditional rhythms from the Niger Delta. After we really step into a strong musical connection, we stop and Abdoulaye gleams, expressing the connection I once desired and decided to abandon at the door of no return. In his French-inflected English, he says with utter excitement:

Stick on that [let’s stay with what we created just now]! This is like the first American African [who] get here and they start to get in liberty and they start to sing in English who still having [have] in the blood dees traditional deep beats ‘n’ melody from Africa and [are] able to sing really in English. Oh that,” he stops himself, “Oh my GOD, it’s beautiful!!! If you can stick on, I see you follow the music good, oooh, you will bring the blues back to the origin. Yeah, Kyra! Oh, this is beautiful. You just bring back the blues on [to] its origin (with an apparent nasal inflection to intensify his meaning).

How ironic. Abdoulaye sounded like a true African American. Perhaps the migration itself is what makes us long for the past. No matter, our journey has just began and I can’t wait to see what else we create.

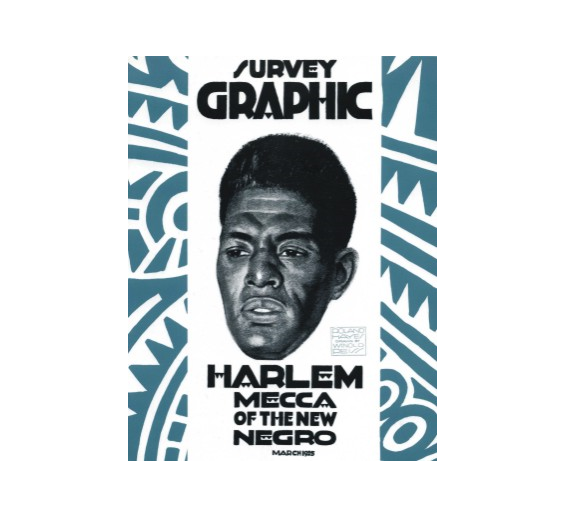

[FOOTNOTE FOR YOU ALL]: James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938), wrote that Harlem was “the great mecca for the sight-seer, the pleasure-seeker, the curious, the adventurous, the enterprising, the ambitious and the talented of the whole Negro world; for the lure of [Harlem] has reached down to every island of the Carib Sea and has penetrated even into Africa” (emphasis added;). I included the cover of Survey Graphic (Johnson 1925, 635) run by sociologists committed to using research to aid social reform (Kirschenbaum and Tousignant 1996). The issue, titled “Harlem: The Mecca of the New Negro,” was the first of several attempts to formulate a political and cultural representation of the “New” Negro and the Harlem community.

Who is Kyra Gaunt?

Kyra D. Gaunt, Ph.D., an Associate Professor of cultural anthropology and black music studies at Baruch College-CUNY. Her book The Games Black Girls Play: Learning the Ropes from Double-Dutch to Hip-hop (NYU Press 2006) won the 2007 Merriam Prize for the most outstanding book in the field of ethnomusicology given by the Society for Ethnomusicology. Selected as one of 40 fellows from around the world to attend the prestigious TED 2009 Conference, “the ultimate brain spa,” Kyra presented her new project “Racism as a Resource (Agree to be Offended).” TEDserves as a forum for “thinkers and doers” to share what they are passionate about. Visit TED.com. Gaunt lectures nationally and internationally voicing transformations of race, gender and generation through song, scholarship and social media. As a consultant for PBS’s Emmy-winning Between the Lions and appeared in the PBS documentary Sweet Honey in the Rock: Raise Your Voice (2005) among other documentaries, she spreads messages that matter beyond the classroom. She is a performer and recording artist in New York City and her CD Be the True Revolution is available on cdbaby and iTunes. On a lighter note, Kyra is a long-time fan of theYoung and the Restless and follow her project Racism as a Resource (for being Courageous and Compassionate). Kyra Gaunt on Twitter Kyra Gaunt’s website.